Apparently Lord Justice Leveson has said that what he most wished to avoid when producing his report on the culture, practices, and ethics of the press, was publishing a document that would be discussed and then put away in a cupboard. I know how he feels.

Apparently Lord Justice Leveson has said that what he most wished to avoid when producing his report on the culture, practices, and ethics of the press, was publishing a document that would be discussed and then put away in a cupboard. I know how he feels.

At the end of last year, someone leaked an email from Bob Ward – spinmeister and chief attack dog at the Grantham Institute – which was evidently intended to stimulate action on an academic message board dealing with ‘science communication’. Bob was a worried man:

The Leveson Inquiry is considering the culture of both the UK Press and broadcast media. No doubt the ‘sceptics’ are bombarding Leveson with anti-BBC propaganda in the same way they did during the early stages of the BBC Trust report. It would be good if there were some balancing submissions to Leveson from sensible psci-commers.

Until I saw this, I had not realised that Leveson might be prepared to poke into some of the murkier corners of the media which Andrew Montford and I have been trying to illuminate for several years. It was also interesting to see that although Professor Steve Jones’ review of science reporting for the BBC had dismissed our submission out of hand, it had evidently caused concern elsewhere among the warmist ranks. This had dealt with the extent to which BBC reporters and programme makers seemed to be in thrall to environmental pressure groups and climate researchers, a problem that has recently matured into 28-Gate.

So far as the Leveson Inquiry was concerned, we did no more than agree that we should make a submission, but there were lots of other things to do and nothing much happened. Then Fiona Fox, CEO of the Science Media Centre, sent written evidence to the inquiry that caused us some surprise. Although the events relating to the climate debate that she described were familiar to us, her version of the facts and the inferences that she drew from them, were surprising. These mainly concerned a very dodgy press release that suggested global temperatures would increase by 11o C by the end of the century and what she considered to be media excesses in reporting Professor Phil Jones role in the Climategate scandal.

This provided the incentive to write to the Leveson Inquiry, so we asked whether it was too late to submit comments on Ms Fox’s evidence, and warned them that our evidence would conflict with that of Ms Fox. To our surprise we received a positively enthusiastic reply saying that the Inquiry would ‘welcome’ such a submission. Would this distinguished, and presumably fair minded Law Lord give a couple of climate sceptics a fair hearing? It seemed possible.

The document we submitted can be found here. It is long, very thoroughly referenced to documentary evidence, and covers the problems we have had with the BBC over the 2006 climate seminar as well as Ms Fox’s evidence. However it would not have surprised me if that had been the last we heard of it. The auto-responses from the ‘inquiry team’ all said that they receive many submissions, but only those that are used would be acknowledged. So morale was given another boost when, only a couple of days later, we were asked for our consent to the submission being published as evidence on the Inquiry website. However we were not called to give oral evidence.

Now, many months later, Lord Leveson has spoke – in four volumes comprising nearly 2000 pages, and goodness knows how many words. He has almost nothing to say about the culture, practices and ethics of the press when reporting on climate change.

Volume 1, Part A, 2.5 – 2.9 addresses a problem raised by various parties described as campaign groups. Under the present Press Complaints Commission (PCC) procedures, it is not possible for a complaint to be made other than by an identified victim. Therefore if you see what you consider to be a misleading report about a matter with which you are familiar, but the inaccuracy cannot be shown to affect you directly, then it is not possible to complain to the PCC. Examples of such ‘generic’ issues in which this situation might apply are immigration, domestic violence, and climate change. The danger of interfering with this situation is, of course, that an organisation like the Grantham Institute – which was set up by a billionaire hedge fund manager with a bee in his bonnet about ‘the environment’ – might choose to bring complaints against any report on climate change with which their benefactor might be expected to disagree. This would do nothing to promote courageous reporting of a controversial subject.

This problem attracted a flood of submissions to the Inquiry and at this early stage in his report Lord Leveson is at pains to reassure their authors that he has read all those that were published by the Inquiry, taken them into account when writing his report, and referred to them where appropriate (Vol 1, Pt A, 2.8), He also stresses that where evidence had not been taken orally as well, this did not mean that the written evidence was in any way inferior. There is no question,he says, of any of the published evidence being second class. This makes some of the things that he says, or fails to say,later in the report even more surprising.

In the meantime, I wonder if Lord Leveson smiled when he quoted this wonderfully complacent little purple passage from Alan Rusbridger, editor-in-chief of The Guardian:

“the simple craft of reporting: recording things; asking questions; being an observer; giving context. It’s sitting in a magistrates’ court reporting on the daily tide of crime cases – the community’s witness to the process of justice. It’s being on the front line in Libya, trying to sift conflicting propaganda from the reality. It’s reporting the rival arguments over climate change – and helping the public to evaluate where the truth lies.” Vol 1, Pt B, 3.2

Sadly, It seems far more likely that the irony of The Graun reporting ‘rival arguments’ over climate change to help their readers ‘evaluate where the truth lies’ was completely lost on him.

When, in the next volume, his Lordship makes another foray into the realms of climate change, he relies on evidence from an organisation called Full Fact. (Vol 2, Pt F, 2.27) The Inquiry website shows that they contributed no less than five submissions and a witness statement. The only reference to climate change I can find in any of these concerns a story in the Daily Mail, apparently relying on figures obtained from the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) website, estimating the amount that energy from alternatives will cost householders. This could hardly be described as ‘misleading reporting in areas such as … climate change’.

Then, at last, it looks as though Lord Leveson will, on page 491, get down to the nitty gritty of the way the ‘culture, practices and ethics of the press’ impact on the reporting of climate change. This is how Lord Leveson launches into the subject:

Similar, but more controversial, concerns have been raised by organisations in relation to the reporting of issues as diverse as climate change and drug addiction. It is unnecessary to do more than touch on these: the relevant submissions are available on the Inquiry website for public scrutiny. It goes without saying that the Inquiry has not undertaken the task of forming its own expert scientific judgment on this material and, in any event, it is unnecessary that it should do so. Vol 2, Pt F, 3.30

Scrutiny of the following paragraphs show that he has touched so lightly on climate change that is seems not to be mentioned at all, although he does say that:

… the public must be in a position to understand what is fact (and therefore to be relied on as such) and what is opinion … There is, of course, no bright line for the way that accurate facts are described, or for the choice of accurate facts that are reported and it is recognised that journalists do not have the same standards of impartiality that affect broadcasters. Vol 2, Pt F, 3.32 – 3.33

There are two points here. Firstly, Lord Leveson does not need to form his own expert scientific judgement in order to determine whether there are problems in the way that climate change is reported, any more than Mr Justice Burton in the High Court needed any scientific expertise of his own to determine that Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth’ was alarmist and misleading. Secondly, his Lordship seems not to have considered the problem of distinguishing what is fact and what is opinion in climate change when nearly everyone claims that their opinions, or speculations, are facts.

However, he does recommend that readers should look at evidence published on the website. When one sees that he cites the Welcome Trust, Sense about Science, Fiona Fox of the Science Media Centre and the UK Drug Policy Commission, but makes no mention of our submission, that rather undercuts his earlier claim that there is no such thing, in his eyes, as second-class evidence.

Much further on, his lordship grapples, very briefly, with the concerns of various defenders of the scientific orthodoxy about ‘false balance’. They argue that,if both minority and majority views in a scientific discourse are reported – for the sake of balance – then this is unfair to the majority who, of course, must be right. Wisely he smartly moves on to other things after pointing out that this may be a problem in some areas of medical research. In spite of introducing the subject by citing climate change as one of the areas where false balance may be a problem, he has nothing specific to say on the subject, which may be wise of him, but surely his remit was to deal with difficult issues like this.

Finally, Lord Leveson bids goodbye to the topic of climate change altogether on page 691, never to return to it:

Examples of scare stories are not limited to health journalism; the reporting of climate change is also susceptible to exaggeration. When a Nature paper modelling climate change projected warming between 2 degrees and 11 degrees, almost all the newspapers carried the latter figure in their headlines, with one tabloid splashing a huge 11 degrees on the front page alongside an apocalyptic image. This was in spite of the fact that the press briefing to launch the paper had all emphasised that the vast majority of models showed warming around 2 degrees. Vol 2 Pt F 9.68

Given that our evidence to the Inquiry provided a link to the press release with which the scientists concerned briefed the press by claiming a possible temperature increase of 11o C, without mentioning the 2o C estimate at all, his conclusion is rather surprising. But one does get the impression here that science may not be Lord Leveson’s favourite bag of tricks. Referring to ‘degrees’ four times in one paragraph without once mentioning what temperature scale they may be recorded in hardly inspires confidence in the sceptical reader.

What is remarkable about this four volume, 2000 page mammoth based on evidence that took nine months to gather, is how little it has to say about one of the most controversial areas of media reporting. In order to prepare this article I used ‘climate change’ as a search string and I have summarised all the instances that I could find.

A first take on the Leveson Report yesterday evening at the GWPF website had this to say:

It was also disappointing that Lord Leveson ignored the arguments and comments made by Tony Newbery and Andrew Montford. In my view this renders the section on science reporting in the report little more than a Science Media Centre press release.

The Leveson Report and False Balance

Those kind word are particularly appreciated, coming as they do from David Whitehouse, for so many years the man at the BBC who told us about science when it was in the news. I don’t remember there ever being any angst about impartiality and accuracy in those pre-Harrabin, pre-Shukman, pre- seminars with activist s posing as ‘the best scientific experts’ days.

But perhaps, just possibly, I have taken a too pessimistic a view how our evidence was treated. The last paragraph of our contribution says:

In this submission we have attempted to draw attention to some of the very complex forces and issues that apply to the reporting of climate research, a field of science that has become heavily influenced by politics, and dogmatic convictions.

Submission to Leveson

Perhaps Lord Leveson did read what we said, and understood it well enough to steer as wide a course round the subject as he possibly could. If so, that was certainly not our intention.

Update 02/12/2012: Andrew Gilligan has an excellent critique of Leveson’s recommendations in The Sunday Telegraph. He is particularly scathing about the risks attending his lordship’s enthusiasm for allowing third party complaints, which I touched on above, This would, as Gilligan points out, open the way for aggressive lobby groups to make editor’s lives a misery any time they publish reports on some controversial subjects with which they did not agree.

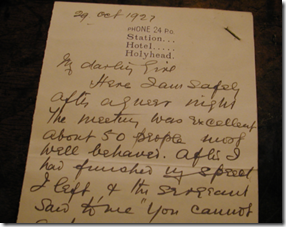

With storms – and even better, rumours of storms – helpfully filling the usual holiday season news vacuum, I thought the letter transcribed below might be of interest. By a strange coincidence, my wife came across it today when sorting through some old family papers.

With storms – and even better, rumours of storms – helpfully filling the usual holiday season news vacuum, I thought the letter transcribed below might be of interest. By a strange coincidence, my wife came across it today when sorting through some old family papers.

Recent Comments