I’ll begin by saying that I do not consider Professor Brian Cox to be an arrogant person, although I only have his TV persona to go by. The television programmes of his that I have watched have been entertaining, informative, full of the excitement of scientific discovery, and thoroughly enjoyable. So this post is not intended to point to a defect in the good professor’s character, but to the mindset that presently afflicts scientists worldwide, and climate scientists in particular. This is a pernicious example of groupthink rather than the hubris of individual scientists, although one might be able to think of a few candidates for exception. They seem to think that their views should be unchallengeable by anyone outside their own profession.

Brian Cox presented his Wheldon Lecture to the Royal Television Society on 26th November 2010 and it was broadcast on BBC2 late on the evening of the 1st December. Under the title of Science: A Challenge to TV Orthodoxy, he spent 40 minutes exploring the controversy that now surrounds the way in which science is packaged by broadcasters for easy assimilation by their mass audiences. By coincidence, perhaps, this thorny problem is also the subject of a review ordered by the BBC Trust, which I have referred to here and here.

Cox has had an interesting career as a pop musician, as a scientist studying particle physics and as a high profile TV presenter. His undoubted talents have recently been recognised by the award of an OBE for services to science.

The subject he chose for his lecture is an important one; our lives are increasingly affected by the outcomes of scientific research and Cox cites an option poll (MORI 2004) finding that 84% of adults receive the majority their information about science from television. It is unlikely, even with the growth of the internet, that this figure has changed very much since then. However the impact that science broadcasting can have on public policy has increased since 2004 because one particular area of research has become inseparable from public policy: global warming. Television is a major opinion former, and presumably this is why Professor Cox chose to focus his lecture on this topic.

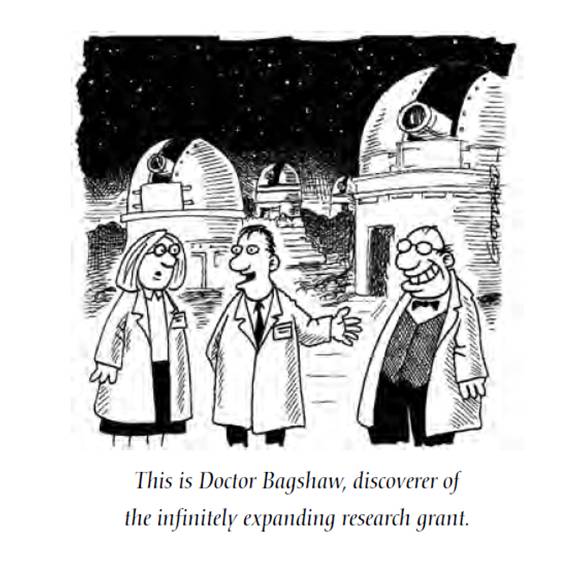

The first part of the lecture is devoted to ground-clearing in preparation for the main thesis, and this is illuminating. Apparently Cox considers that the current impact of science on public policy – particularly global warming – places great responsibility on broadcasters who cover this subject. Strangely, he makes no mention of the infinitely greater responsibility that this places on the scientists who brief the media about their work.

He then reveals that he does not consider that there have been any ‘serious deficiencies’ in television coverage of science. This is a point of view that appears to be at odds with his patrons at the BBC in view of their decision to hold an investigation in the wake of the Climategate scandal and a welter of criticism from the general public and the blogoshere. And If he is unaware of any deficiencies, I wonder why he chose to devote most of his lecture to the problems that broadcasters face when dealing with this subject?

Turning to the influence that television science broadcasting had on his own choice of career, Cox holds up Carl Sagan’s Cosmos series as a glowing example, describing it as ‘thirteen hours of lyrically [and] emotionally engaging and accurate and polemical broadcasting’. Unfortunately, he is misusing the term polemic here, and that is important as this word occurs no less than ten times in his lecture as he sets out his arguments, and it’s usage is crucial to his conclusions. A polemic is a verbal attack and not, as Professor Cox seems to think, merely the expression of a point of view[1].

After worshipping at the feet of Sagan, the next item on Cox’s list is defining science; no mean task as an aside in a single lecture, and not surprisingly the effort is superficial and unsatisfactory. Having acknowledged that this task ‘is not easy in a historical context’, he suggests that ‘vast amounts of drivel have been written about the subject by armies of postmodernist philosophers and journalists.’ Sweeping such trivialities aside, Cox settles for a brief clip from a rather light-hearted lecture by physicist Richard Feynman in which he describes the scientific method. It is certainly an example of entertaining television, but comes nowhere near ‘defining science’. But this still leads to the following conclusion:

To my mind, science is very simple indeed. Science is the best framework we have for understanding the universe.

Of course when someone describes a complex subject as being ‘simple’, warning flags should always go up. Almost invariably the person who uses this term is being very selective in the way they are formulating their opinion. In this case it is not clear whether Cox is using the term ‘universe’ in a purely astronomical sense – as in the mechanics of the universe – or in a much broader sense to cover all aspects of existence.

Since The Enlightenment, science has certainly gone some way towards replacing superstition, religious belief, and fatalism as a means of explaining the phenomena that surround us, but it is still a long way from doing so completely. On a worldwide scale, atheism remains a minority point of view, and scientists would do well to humbly acknowledge this fact rather than claim a position of supremacy and infallibility for their profession that many would dispute.

In the film clip Feynman stresses that, if a scientific proposition is not supported by observation and experiment then it is wrong regardless, as he says, of how ‘beautiful, the idea may be’, or how eminent its author may be. Cox amplifies this by saying,

Authority, or for that matter, the number of people who believe something to be true, counts for nothing.

[and]

… when it comes to the practice of science, the scientists must never have an eye on the audience. For that would be to fatally compromise the process.

This is a hostage to fortune, for without the notion of consensus and claims by eNGOs and politicians for the authority of the IPCC, promotion of anthropogenic global warming would never have cleared the launch pad. The most startling ‘findings’ in recent IPCC reports are not based on the scientific method at all, but on expert judgement by the authors, and the Climategate emails have revealed an obsessive concern among climate scientists with the response of their audience.

Having started to dig himself into a hole, Cox then redoubles his efforts recounting an incident in which he made a dismissive on-screen reference to astrology as being ‘a load of rubbish’, which resulted in complaints to the BBC from ‘all over the web’. The BBC issued a cautious statement that almost amounted to an apology, saying the views expressed in the programme were not those of the BBC, but of the presenter, a response that Cox considers to be inadequate:

Now, that’s a perfectly reasonable response on the surface. In fact, you could argue that it’s correct. Because a broadcaster shouldn’t have a view about a faith issue which is essentially what astrology is. The presenter can have a view, and I was allowed to have a view. What I did was present the scientific consensus.

But he goes on:

I think, however, that there are potential problems with broadcasters assuming a totally neutral position in matters such as this.

Cox then moves on to use a clip from a news item about concern over the use of the MMR vaccine. In this Ben Goldacre (of Bad Science fame) gives his views on this controversy citing a Danish study showing that there has been no increase in autism among children who have received the jab, saying:

You’ve not heard about research like this, because the media chose not to cover the evidence that goes against their scare story.

This message, and its relevance to media coverage of anthropogenic global warming (AGW), seems to have passed Cox by. Instead he castigates the broadcaster for concluding the piece with a caveat that these are Dr Goldacre’s views only, in spite of his being a qualified doctor and having based his opinion on peer reviewed and published research. In support of this criticism he cites a US news anchor, Keith Olbermann, as follows:

… obsessive preoccupation with perceived balance or impartiality [is] worshipping before the false god of utter objectivity. His point was that by aspiring to be utterly neutral, it is easy to obscure the truth. And the BBC’s editorial guidelines state that impartiality is at the heart of public service and is at the core of its commitment to its audience. I’m sure that very few broadcasters would disagree with that.

This reference is striking because I have seen precisely the some argument used by the BBC to justify its anything-but-neutral position on anthropogenic global warming (AGW). There is a certain irony too in using the opinion of a US broadcaster in this way given that so many North Americans seem to envy the standards applied to public service broadcasting in the UK.

On the specific point that Olbermann makes, being ‘utterly neutral’ is obviously far less of a threat to impartiality than not being neutral. And the suggestion that being neutral may obscure the truth – which is the crux of Professor Cox’s lecture – implies that the broadcaster will necessarily be able to determine what the truth is. This conjecture becomes even more problematic when the means by which this feat might be accomplished are considered.

In Cox’s view, reporting science should hold no such dilemmas for the broadcaster: all that is necessary is for complete reliance to be placed on the peer review process. That which is peer reviewed should be the sole reference point for reporting science, and any contrary views should be disregarded. This position is arrived at by having implicit faith in the peer review process, which may for all I know be justified if, like Professor Cox, you are a particle physicist, but it is unlikely to impress anyone who has cast a critical eye on climate science, where political and ethical considerations seem to carry at least as much weight as robust findings. But this is not the place for a detailed discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the peer review process. Instead, here are some of the propositions which Cox uses to back up his argument:

In science, we have a well-defined process for deciding what is mainstream and what is controversial. And it has nothing whatsoever to do with how many people believe something to be true or not. It’s called peer-review.

Peer-review is a very simple and quite often brutal process by which any claim that is submitted for publication in a scientific journal is scrutinised by independent experts whose job it is to find the flaws.

This is the method [peer review] that has delivered the modern world. It’s good. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the current scientific consensus is of course correct. But it does in general mean that the consensus in the scientific literature is the best that can be done given the available data.

Now you may see there that I’m redefining what impartiality means. But the peer-reviewed consensus is by definition impartial. To leave the audience with this particular kind of impartial view is desperately important. We’re dealing with the issues of the life and death of our children and the future of our climate. And the way to deal with this is not to be fair and balanced, to borrow a phrase from a famous news outlet, but to report and explain the peer-reviewed scientific consensus accurately.

So for me the challenge for the science reporter in scientific news is easily met. Report the peer-reviewed consensus and avoid the maverick, eccentric at all costs.

Such faith in the reliability, independence, and impartiality of peer review may be justified in the field of particle physics where, I assume, political and ethical considerations have a very minor role. So far as climate science is concerned, it flies in the face of what has been learned from the Climategate emails, and much else that has happened in this discipline during the last decade. How many news stories have we seen citing sensational ‘new research’ that has swiftly been discarded? Predictions of massive sea level rise by the end of the century, an 11o C rise in global average temperature over the same period, the vanishing snows of Mount Kilimanjaro and the drying-up of Lake Chad, the imminent demise of the Himalayan Glaciers, slowing of the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) with the onset of a new ice age for Northern Europe, and of course that poster-child of the third IPCC Assessment report, the Hockey Stick graph. One could go on and on.

There can be little doubt that Cox is indeed redefining impartiality, and in a way that brings us back to the sub-title of this post – an exercise in arrogance. He seems to be telling us that journalists and programme makers who report science should be guided entirely by the scientific community, and leave any critical faculties they may have at home. If this is to be the new standard for impartiality in broadcasting about science, or even a new world order, then who scrutinises the world of science? And lets not forget the Feynman clip that Cox used in his superficial attempt to ‘define science’ at the beginning of his lecture. The great physicist makes no mention of peer review, but there are strictures in both what he says and Cox’s interpretation of it that rule out authority and consensus as being relevant to the scientific method.

Having cleared the ground, the professor now moves on to the red meat of the lecture; climate change.

This is heralded by a clip from The Great Global Warming Swindle (TGGWS), which Cox dismisses as ‘bollocks’, which does him little credit either as a scientist or a TV presenter. On the other hand he accepts that such programmes should be allowed to be broadcast – one gets the impression that he thinks he is being rather daring here – so long as they are suitably labelled, not as ‘bollocks’ as one might expect, but as polemics rather than documentaries, which Cox seems to think amounts to something similar, but with a warning that it’s probably all rubbish.

In the case of TGGWS, the description ‘polemic’ may be justified. Durkin’s film was undoubtedly a vehement attack on contemporary climate research, but apparently Cox would like any factual broadcasts that do not adhere to mainstream views approved by the scientific community to be branded in this way. Presumably this would mean that a programme about the views of Michael Mann could be promoted as a documentary, while one about the views of Richard Lindzen would be a mere polemic, thereby undermining the credibility of that eminent scientist before the audience even become aware of what he has to say. And this raises a new problem, which Cox steers well clear of.

Climate scientists, and particularly the IPCC, have failed to acknowledge the massive uncertainties that are attached to much climate research. This, of course, feeds through into broadcasts where journalists and program makers are unwilling to acknowledge uncertainly for the reason that Ben Goldacre identified. Why water down an eye-catching prediction by saying that it may never happen when there is no danger of the scientists concerned complaining? But under reporting uncertainty is as misleading as misreporting conclusions.

Even Cox expresses some concern that his approach may be Orwellian, but quickly backs off by saying that he doesn’t really know whether it is Orwellian or not, which makes one wonder why he raised the issue in the first place. Unsurprisingly, he quotes a passage from Nineteen Eighty-Four about history constantly being re-written so that nothing remains on record that cast doubt on the infallibility of The Party. He may have chosen the right author, but the wrong book. In Animal Farm, the precursor of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the dim but compliant sheep are portrayed as the ruling pig’s most effective weapon in stifling opposing views and awkward questions. They can be drilled to bleat any slogan persistently enough to drown out dissent. I hesitate to draw any parallels between the arrogant culture that pervades climate science and the pigs, or between broadcasters and the sheep, but the temptation is great. Cox’s plea that broadcasters should retail only what scientists tell them is acceptable makes it very, very tempting indeed.

By this stage in the lecture, one might begin to wonder how much serious thought Cox has given to his subject, or whether he has been influenced by the views of the BBC in reaching his conclusions. As a scientist, surely he should not attempt to draw an analogy between the way in which broadcasters should treat climate scepticism and the way they should treat those who believe in astrology or question evolution. This is another line of argument of which the BBC is fond, but it makes no sense; the issues are quite different. No institution such as the IPCC is involved in debates about astrology or evolution. Tens of thousands of delegates do not flock to Copenhagen or Cancún to discus these matters and formulate a world policy, neither astrology nor evolution are new ideas, and scientists are not being funded to the tune of countless billions to conduct research in these fields.

Cox’s peroration begins with these words:

So what are my conclusions about the challenges of presenting science on television?

Well, firstly, scientific peer-review is all-important. It’s not possible for a broadcaster to run a parallel peer-review structure, but it is possible for the broadcaster to seek out the consensus view of the scientific community. This is the best that can be done and appropriate weight should be given to it in news reporting.

Documentary is different because polemic is a valid and necessary form of filmmaking. But having said that, the audience needs to know whether they’re watching opinion, or a presentation of the scientific consensus. And whilst I acknowledge that this is extremely difficult to achieve in practice, it is something that filmmakers and broadcasters must strive to do.

Cox’s final message to broadcasters is clear: they should do what scientists tell them to do and not trouble their pretty little heads with anything that might be too difficult for them to grasp properly. As to listening to ‘mavericks and eccentrics’ who question the scientific consensus established by a supposedly interdependent and reliable peer review process, that would be foolish in the extreme, like listening to astrologers or creationists. And screening the views of people who scientists might consider to be reprehensible in such a way that audiences would be allowed to make their own mind about the credibility of what they are being told would be a betrayal of the broadcasters duty to comply with a re-defined kind of impartiality; a kind of impartiality in which the broadcasters determine where the truth lies on the basis of the majority view of those who are being challenged.

This is, of course, a supremely arrogant point of view, but the scientific community seem to have convinced each other, and themselves, that society should confer such authority on them. One can hardly blame Professor Cox for falling into line.

[1] A strong verbal or written attack on someone or something. (Oxford Dictionary of English)

My Affair with George Monbiot: Part2

The career of George Monbiot has been meteoric – coming down to earth in a shower of sparks, and leaving a charred hole where the Guardian’s top investigative journalist used to be. From Paul Foot to William Boot in a few carbon-shedding steps.

(For non-Brits: Foot was a campaigning journalist at Private Eye and the Guardian. William Boot is the journalist hero of Evelyn Waugh’s novel “Scoop”, who, after a disastrous episode in which he is sent to Africa to cover a revolution, ends up back in the office writing Nature Notes).

In February 2009 Monbiot initiated a new format blog at Guardian Environment with an attack on Telegraph journalist Christopher Booker. In the article, entitled « Booker’s work of clanger-dropping fiction » he accused his colleague of writing “complete trash, and provided a list of seven claims in an article by Booker which Monbiot attempted to refute.

A second article, two days later, entitled “Pure rubbish: Christopher Booker prize” featured a photo captioned “Christopher Booker prize 2009 offered for producing clap-trap about climate change”. Readers were invited to nominate articles, and George explained:

There is a note at the bottom of the first article saying “this blog has been amended”. What has been altered is the word “Bullshit” which featured in the original article, and is still visible in the photo of the “award” in the second article.

Of the supposed errors by Booker: Continue reading »